In my neighborhood there is a tree I pass on my way to the park that has grown over the metal bars someone erected around it years ago. The metal bars were set there for protection, I suspect, but from what, I’m unsure. It’s the only tree with its own fence on the block. It’s not that the posts have penetrated the tree; the tree has absorbed the metal. The wood flows around it. This doesn’t seem to have unsettled the tree. Each spring its leaves are abundant. I wonder how long before the container becomes the thing contained?

The relationship of the vessel to its volume is fundamental, but when the vessel holds a tree the balance of the interaction becomes more complex. The tree either outgrows its container, or the tree is pruned sufficiently to dwarf its growth and maintain an equilibrium. In other words, the relationship is not static, but dynamic, and it’s compelled by the conditions of the environment, which may be both natural (sun & rain) and cultural (clippers & saws). That the materials can be influenced, molded, encouraged to respond to the hand of the artist means that this relationship can be a sculptural one. For Ben Keating, it is.

If there are two materials Keating understands with intuitive clarity, they would be molten metal and fertile soil. Keating is a person who operates a foundry as well as he tends a garden; a person who teaches others how to work in a foundry and whose garden feeds his neighbors; a person who rescues saplings he finds covered in plastic, and a person whose home is the sum of what he’s built. When Keating talks about the fires of his furnace as he handles the delicate new buds on a tree that is more than two centuries old, you hear the kind of passion that only comes from a heady mixture of deep knowledge and limitless curiosity—a combination that rejuvenates itself endlessly.

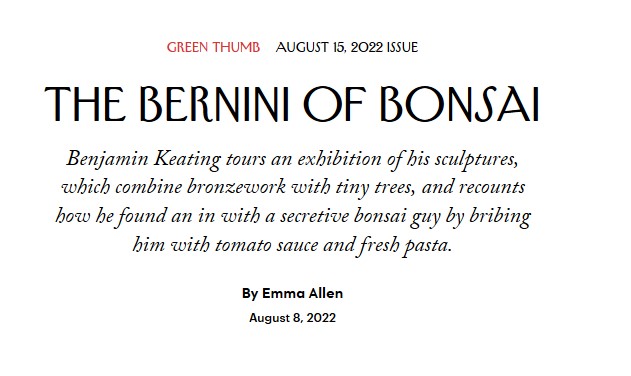

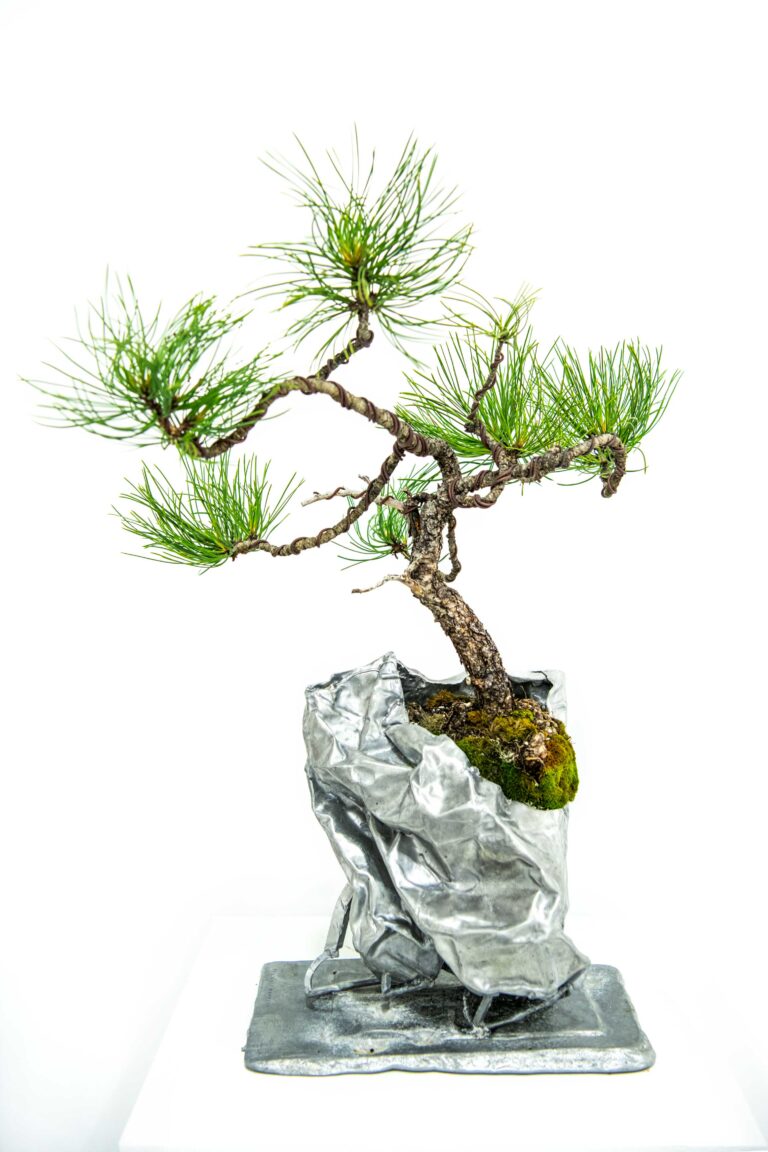

Keating walks as he talks to me about the species of his trees and how he’s using different types of metals. Like precious stones, the small trees are set in containers that fit them just so. In one I admire how the soft organic texture of the mossy mound at the base of the tree is accentuated by the shine of aluminum that surrounds it. In another I’m transfixed by the way sculpted metal frames a small pine. Some of the forms Keating casts are domestic—a pair of old sneakers, now bronze—but mostly he is piecing together crude shapes to create different structures of ranging complexity. How these shapes correspond and establish a sense of balance with the verticality of the tree is a measure of Keating’s material intelligence and cunning aesthetic sensibility.

Artists have traditionally applied the concept of the “readymade” or the found object to manufactured things. For certain artists the point of the gesture is to remove the hand of the creator from the process of creation. For others it’s a means of socio-cultural critique. Neither quite applies to Keating, whose use of a living tree is less a conceptual gambit then a formal innovation. For Keating the tree is not a symbol or a metaphor communicating ideas about nature; it is nature. In a sense then, the natural world is Keating’s collaborator, for its energies are responsible for the tree’s very being, and by extension those energies imbue the sculpture. It is new territory for the artist, and that’s exciting.

Little gives the impression of pre-conception. Keating knows his process, but he doesn’t let it drive his decisions. Rather, he makes his choices based on the qualities of the materials—a particular tree, a specific metal—and follows his gut. The results are meant to be a discovery, a surprise, which means that while Keating’s recent body of work feels cohesive and interconnected, it simultaneously achieves tremendous variety.

The seeking quality of Keating’s aesthetic process is a reflection of the artist’s disposition. He is one who sees more than many because he looks closer than most, and he questions both what he understands and what he’s only just learned. As is one’s life, so goes one’s art. Keating creates for the thrill of creation, for the sensual pleasure of aesthetic form, for the challenge of it all. The work embodies those impulses because it is from them that the sculpture emerges.

Time and touch: one you feel with your body, the other you feel in your body. In one there is a sense of immediacy and directness (I’m touching this surface) while in the other there tends to be a sense distance and response (I’m touched by your gesture). Keating’s sculpture achieves both because it is work that actually insists on being touched. After all, the tree must be attended too. And the tree will grow. It will transform, however subtly, as all living things do, and that slow growth means the work of art continues becoming something new even as it remains itself, ever onwards. ~ Charles M. Shultz